In my previous blogpost, I briefly shared about one other solution that could help in dealing with the shortage of safe water, which is the provision of water in plastic sachets. While that method may have its pros and cons as discussed, it is not the ONLY way. There is also a plethora of other strategies undertaken by the African government to help with the impending water crisis that the continent is going through. It is imperative to note that governments do not work alone when implementing these strategies. Often, (an)other stakeholder(s) will be partially responsible during the initiation process too.

Lake Volta and Akosombo Dam (Image source: Ghanaweb.com)

For this post, I will focus more on the integrated water resource management (IWRM) strategies that are undertaken in the Volta Basin in West Africa. First, IWRM is an approach that seeks to manage water resources in an all-rounded way, ensuring that all details regarding the different dimensions and perspectives of both water quality and quantity are accounted for, thus allowing for suitable assessments to be made (Savenjie & Van der Zaag, 2008). The Volta basin is shared by six riparian countries, which includes Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Mali, Togo, and Ghana, where its total population is estimated to be slightly above 14 million in 2011 (GWP.org, 2011).

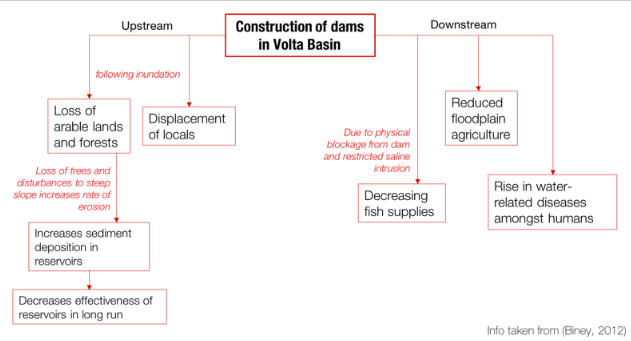

Even though the Volta transboundary system is one of the biggest river basins in the continent, it lacked legitimate measures between the riparian countries for a long time (Outlines and Principles for Sustainable Development of the Volta Basin Final Report, 2014). Because of this, those in-charge of water resources in the respective riparian countries founded the Volta Basin Authority (VBA) on 16 July 2006. The Volta basin has gone through several development in the last 50 years, leading to negative consequences in the socio-economic sphere and the environment. The diagram below highlights the impacts resulting from the construction of the Volta basin dams meant to generate hydropower for the surrounding countries.

Figure 1: Impacts arising from dam construction in Volta Basin (Source: Biney, 2012, pg. 19)

Besides the dam’s consequences, increasing agricultural production, unsustainable fishing methods, and forecasted impacts from climate change has led to growing worries about the future of Volta basin’s ability to provide enough water for the six different countries it currently supports. Hence, this worry led to the creation of a strategic plan by the VBA, with fiscal support from the World Bank and the Global Environmental Facility (BusinessWorldGhana.com, 2016). This plan, which covers the years 2010 to 2014, has 5 objectives which it aims to achieve:

1. Strengthening policies, legislation, and institutional framework

2. Strengthening knowledge base of the basin through establishment of the VBA Observatory for Water Resources

3. Coordination, planning, and management

4. Communication and capacity building for all stakeholders

5. Effective and sustainable operations

(Biney, 2012)

Based on the above objectives, the VBA had hoped to bring about changes to the way water was distributed and used amongst the riparian countries that surround the Volta Basin. According to the Water and Nature Initiative case study on the Volta Basin, the main focus of the VBA on Burkina Faso and Ghana was mostly on water governance which worked on three different scales. Firstly, on the transboundary scale level, a code of conduct was developed by authorities of Burkina Faso and Ghana to ensure that both countries agreed on the management of their shared water resources. Likewise, a transboundary committee was also formed.

Figure 2: Code of Conduct Framework (Source: Welling et al. in WANI case study)

Secondly, on a national level, forum meetings were organized to establish local partnerships between water authorities of Burkina Faso and Ghana. These forums were key in providing a platform for coming up with initiatives that are both reactive and proactive to changes in national and local concerns. Lastly, on the local level, a local transboundary committee was also formed in 2008, with support from WANI. In more recent times, the VBA started its journey towards initiating a Water Charter for its existing IWRM. The Water Charter’s vision is as follows in quotes:

“A basin shared by willing and cooperating partners, managing the water resources rationally and sustainably for their comprehensive socio-economic development.”The aim for this venture is to provide an established tool to boost inter-state collaboration on the shared river basin for member countries’ collective benefits. The reason for this evolved initiative is due to the negative outcomes arising from the previous 2010-2014 strategic plan, which underlined several environmental issues that were not formerly tackled. These included changes in water quantity and seasonal flows, degradation of ecosystems and deterioration of water quality. Likewise, climate change and its impacts, as well as incompetent management team also did not help in improving the transboundary water situation. As such, the new goal was to augment the VBA’s management capacity with regards to transboundary water resources, with a focus on development of the Water Charter. The following diagram summarises the development process.

Thus, this post has highlighted a way in which water resources are managed, which is through an integrated transboundary water governance system. However, due to the massive scale this management strategy entails (in terms of the length of implementation, the number of stakeholders involved, and the monetary and opportunity costs), it is difficult to ascertain its success in the short-run. This is especially so with the dynamic nature of IWRMs, which evolve together with changes in national and communal interests. Then again, after researching so much on the basin and its accompanying IWRM(s), I truly believe that with time, the six riparian countries involved will eventually come to benefit greatly from the VBA's strategic plans, as long as the stakeholders in-charge maintain their drive towards achieving its goals. As mentioned by the executive director of the Water Resources Commission in Ghana, Ben Ampomah, "the authority (is) growing steadily and currently (is) better poised to handle the challenges" faced by the countries sharing the Volta Basin.

Comments

Post a Comment